The adoption of Electric Vehicles (EVs) in the UK is still at the stage where their mere presence creates interest, ranging from the reasonable – questions about range, infrastructure and charging times – to the incredulous, “An electric car, in Scotland – are you f***ing mad?!”. So this is where we find out if the latter is in fact correct, or if our own judgement in buying the thing has stood up to the test of the real world. By which I mean a month-and-a-bit and 2,000 miles so far.

Firstly then, how far does the beast take us before running out of electrons?

Range

The Tesla Model 3 Performance has a WLTP-certified range of 329 miles, with the US EPA qualifying it for 310 miles in mixed driving. Now we’re all familiar with the equivalent consumption claims for combustion-engined vehicles, where the quoted figures simply aren’t achievable in day-to-day use – typically falling 20-30% short. So it’ll be no news that EVs are no different in the real world – the headline figures here are that, if we always drove at or below the national or motorway speed limits and didn’t do any high-acceleration overtakes, we’d actually come close to the claimed figures, with 280-300 miles being readily achievable. By backing off another 5-10mph, I think we’d pretty much get there.

But that’s not how I usually drive: in ambient temperatures of 8-14ºC, mostly when raining (wipers on and greater rolling resistance) and dull (lights on as well), I’m getting a range of 240-270 miles, driving in an entirely ’normal’ and progressive fashion, and making use of the car’s acceleration to get past dawdling tourist traffic on our Highland roads. If we allow an effective battery capacity of around 74kWh, that means I’m using 270-310Wh for every mile travelled, peaking at 330Wh/mile if making ‘serious’ progress.

As with any car, making fuller use of the available performance quickly hits consumption, but even when playing quite extensively, I’ve not managed to drop below 220 miles range (335Wh/mile).

But remember this: with an EV, you start every day with a full tank, or rather, a battery charged to the limit you’ve previously set – Tesla, like most EV manufacturers, suggests keeping maximum charge to 80-90% unless you’re going on a long journey where you’ll need the range.

So a 290 mile business trip last week went something like this:

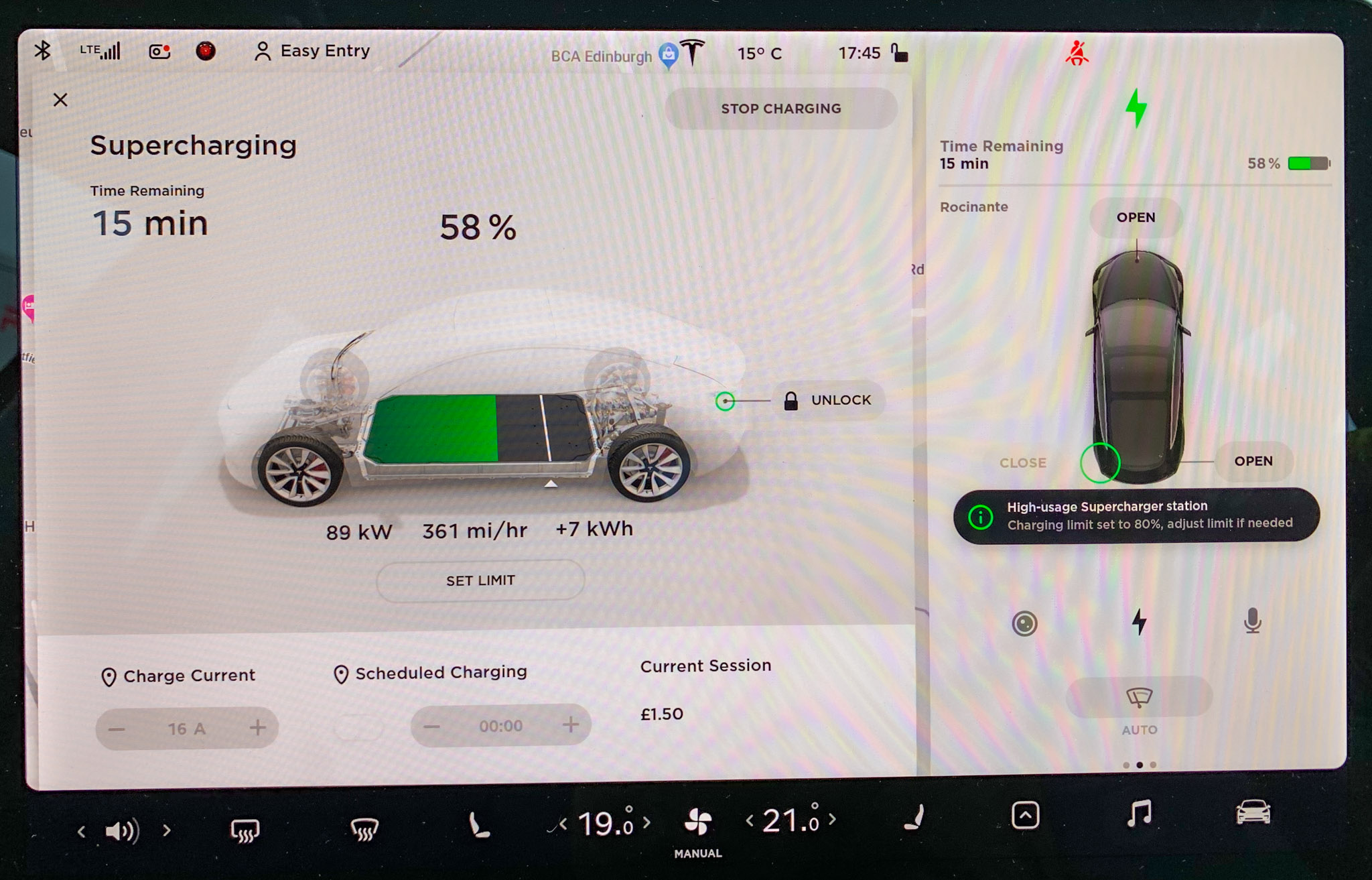

Leave home at 8ºC ambient, with the car charged to 90% overnight and drive 125 miles to Inverness, over 50 miles of twisting and winding mountain roads, until we picked up the A9 North of Bruar. Thereafter, it was a 75 mile blat up the A9, mostly on Autopilot in the 60mph average speed camera zone, with the occasional blast past slow traffic on the dual carriageway sections. We arrived in Inverness with 49% battery left and plugged into the client’s 22kW charger (and if it hadn’t been available, we had plenty of range to get to either the Aviemore or Perth Superchargers (150kW), or indeed to any of the Rapid (50kW) chargers installed as part of the Electric A9 scheme.

By the time we left the meeting, the car was back to the charge limit I’d set of 90%, and we headed back down the A9 to Perth, again mainly on Autopilot (of which, more anon). Having dropped a colleague at Perth railway station, the car was telling me that I’d arrive home with 24% battery left. Given that we’re still waiting delivery of our home charger, recharging from our normal mains socket would have taken ages, so I dropped in to the Perth Supercharger: by the I’d walked to McDonald’s, ordered and chugged a double espresso and walked back to the car, it was back over 80%, so I headed home. Plugged in on arrival, set the charge limit back to 80% and the car was back up to charge by breakfast.

The only charge I paid for was the top-up back home, which came to about £6 overnight on our temporary and expensive tariff. The charge in Inverness was free, courtesy of the Scottish Government, and the Supercharge at Perth came off the mileage credit that came with the car. Had I had to pay for the lot however, it would have cost me around £17. In its diesel predecessor, it would have cost £60 in fuel alone. Result.

Other trips we make reasonably regularly are to Manchester and/or the Yorkshire Dales, and our journey to the latter goes something like: 30 miles of twisty highland roads, with lots of overtaking of slow tourist/agri traffic, which does burn amps (averaging about 330Wh/mile). Thereafter 148 miles of motorway at 75-80ish (310Wh/mile) and I arrive at Tebay Services Supercharger with 20Kwh left. A 20 minute charge there, on a bad day gets me 30kWh back, so another 27 miles of twisties to Wensleydale leaves us with 120 miles or so of running around without having to charge again. In fact, I’ll hopefully plug in overnight on a 7.4kW destination charger and be back up to full strength by the morning. For Manchester I’ll do the same, except I’ll give it another 10 minutes at Tebay, giving me 45kWh back, so I’ll then do another 110 motorway miles, plus 12 miles of urban trundling, arriving at destination with 27kWh left (100+ miles of urban range).

Now cold does impact EV range, both by increasing the demand for heating, lighting etc and the effect of cold weather on the battery itself. There, the general reckoning is that you can expect a 10-15% hit on range in a typical British winter, and 20% if you live in Norway.

Given that none of those scenarios results in the effective worry-free range dropping below 200 miles, which was our marker for ‘in all circumstances’ range, we’re quite happy: for us, the key metric for buying an electric car was that it’s range comfortably exceeded that of our bladders and that it was able to recharge to a decent level in the time then taken to empty said bladders and refill them with coffee.

We’re also finding that the Tesla is matching our expectation that it’s overall driving efficiency would prove considerably better than that of most, if not all, other EVs.

So we’re quite happy with the distance we can get in the thing. Where things aren’t (quite) so rosy is when it comes to the public charging infrastructure…

Guilty and Charged

Now there are no grades of electrons – no diesel, no premium, no special additives, the differentiator being in the rate at which those electrons are shuffled into your vehicle’s battery. As of 8 October 2019 1 the UK has 15,592 charging devices, with 26,635 connectors, at 9,812 locations, with 464 added in the last 30 days. Of those 2,537 devices with 5,930 connectors at 1,755 locations are what are called ‘Rapid’ DC chargers, that can deliver DC current at 50kW or greater. Most public Rapids also provide 43kW/63A AC for Renault Zoes and Kangoos, although they will provide a lower AC charge to other vehicles. It is considered poor manners to plug an EV that will only take 7-11kW in to an AC Rapid and then wander off. Of the DC Rapids, 377 are Tesla Superchargers. With a modern EV, a domestic 7.4kW AC ‘Fast’ charger is fine for an overnight charge but, when you’re on the road and need a running top-up, you’ll need to look for a Rapid. Our Model 3 will charge at 11kW from an AC source, and up to 250kW from a DC source. Rapid beats Fast, every time.

This is where things get problematic, although the picture is improving: too many of the public chargers already installed are low-speed AC chargers, of 3-7kW: OK for topping off the battery on a PHEV, but of little use to full EVs. Not only that, but the entire public charging network is spread across many different network providers. That wouldn’t be a problem if they worked like petrol stations, where you have a common payment mechanism called a debit card. D’uh. Not so with EV charging: most networks require either an app or an RFID card to start a charging session. For charged networks you then have a debit card registered, and you pay that way, per kWh, time connected, subscription or any combination. Other networks are subsidised, and there’s no charge, but you still need the app or RFID card. There are far too many different systems at the moment – it’s rather as if every petrol station operator had their own payment system and wouldn’t accept anyone else’s. Newer chargers are starting to work ‘normally’ – ie just with your contactless payment card, but it’ll be a while before that’s universal. By far the most reliable though are Tesla’s Superchargers – you just plug your Tesla in, your car starts charging, at up to 150kW (and soon up to 250kW), and it automatically charges your account. That’s worth a lot, even if the network still needs a lot of expansion and suffers from queuing at the most popular sites.

It gets worse though: a number of the public chargers are poorly maintained and too often are out of action. Then there’s the issue of vehicle compatibility: not simply on the charge sockets – where most chargers are now standardising on the Type 2 connector, although many also still support the Japanese ChaDeMo socket that Nissan’a Leaf uses – but on just making the things work with your car. There, the problem is one of flaky implementation of the charging protocols, by both the charge point and car manufacturers. Ecotricity, who have had a monopoly on non-Tesla charge points at UK service stations, have a particularly poor reputation for both reliability and compatibility, and the Jaguar i-Pace seems to suffer more than most from compatibility problems. With the Model 3, compatibility issues seem to be fewer, often related to the order in which you plug in the charger at either end and when you wave your card at the system.

Then there’s the service itself: the ChargeYourCar system, whose web site and app underpin the Scottish Government’s ChargePlaceScotland network, offers an embarrassingly poor quality of both web site and app – you’re invariably out of luck unless you have one of their £20 RFID cards. Welcome to software design, circa 1985. Fortunately their telephone helpline is actually helpful and can often get a charge going remotely. Another issue is the poor quality of rural mobile data networks in the UK: too often either or both of the charger itself or the user’s phone can’t get a signal to get a charge under way. If that sounds somewhat damning, it is, but I will note that – so far – there’s been no time when the failure of a charger has caused us any range anxiety. Things are also improving, especially with the start of the rollout of the Ionity network in the UK, the first network that approaches or surpasses Tesla’s in terms of the charge its stations can deliver. However, with only two sites live to date, it’s got a way to go yet. So it’s still Tesla for the win, and until we have a truly universal Rapid charging infrastructure, it should remain a major consideration for anyone planning to buy an EV with serious distance in mind.

Put all of that together, and we have a car which, so far, has more than adequately fulfilled our needs, exceeded expectations in most areas and whose utility will only improve further as the infrastructure improves. It’s Future Imperfect, but it’s here, now.

Up next: Part 3 will move onto the autonomy features of the Tesla and Part 4 the Controls and Interior.

If any of this inspires you to actually go and buy a Tesla, please help me offset the costs of running this site without adverts by using my referral code: that way we both get 1000 free miles of Supercharging: https://ts.la/richard94955

Leave a Reply